|

CAFC判決

BASF Corporation v. Johnson Matthey

Inc.

2017年 11月

20日

URL LINK

Nautilus判決後の112条第2項の明瞭性に対する判決。

「・・・に有効な」という表現

OPINION

by JUDGE Taranto

Summarized

by Tatsuo YABE – 2018-01-06

|

|

Nautilus(2014年の最高裁判決)後の112条第2項の明瞭性に関する判決である。Nautilusは、2014年までのCAFCの明瞭性の判断基準(クレームが解消不能

“insolubly ambiguous”な程度まで不明瞭な場合に112条2項違反とする)を否定し、新基準を判示した。Nautilusの新基準は、「明細書および経過書類を参酌して、合理的な確証(“reasonable

certainty”)をもって、当業者が発明の権利範囲を理解できない場合には112条2項の要件を満たさないとした。

|

本事件の争点は、USP8524185特許クレーム1の”composition

effective to catalyze (触媒作用を起こすのに有効な材料組成物)”という用語は、Nautilusの基準、即ち、明細書の説明及び当業者の知識に鑑み、どのような材料組成物がそれに該当するのか当業者が合理的な確証をもって理解できるのかである? 地裁は問題となった用語は112条第2項の明瞭性の要件を満たさないとして185特許を無効と判断した。CAFCは明細書の開示及び経過書類に鑑みクレームは明瞭であるとし地裁判決を破棄差し戻した。CAFCが判決に至った理由は、185特許における発明(引例と識別された特徴)は触媒作用を起こすのに有効な触媒の特定ではなく、材料組成物Aを含む触媒1と材料組成物Bを含む触媒2の配置(一部重層構造)の仕方である。さらに、明細書に材料組成物Aと材料組生物Bに対応する触媒が詳細に例示されている。

|

Nautilus判決(2014年)によって112条2項の明瞭性の基準は文言的には厳しくなった(“insolubly

ambiguousの場合にNG” à

“reasonable certaintyでないとNG”)ことは明白である。しかし、Nautilusの新基準によって、旧基準では明瞭とされたであろうクレームが不明瞭と判断されたことを明示する顕著な判例を少なくとも筆者は知らない。本判決もその類に属さない。しかし、少なくとも本判決から学べることは(再確認できることは)、Nautilus判決後においても、クレーム用語の明瞭性は当業者の一般知識を考慮に入れて判断すること、112条2項要件を満たすにはクレーム用語に対する明細書のサポートが重要であること、さらには、クレームされた発明の本質部分(引例との差異を主張した特徴)ではない特徴に対する明瞭性の要件はやや緩いという点にある。

|

さらに、(Prosecutionの実務者には釈迦に説法であるが)審査段階における112条2項の審査基準とNautilusの新基準とは異なるという点である。即ち、審査においてはクレームの解釈にBRI基準(合理的に最も広い意味合い)で解釈するのに対して訴訟では審査経過書類に鑑み解釈する(BRI基準は適用されない)。さらに審査においては出願人はクレーム補正が可能なので審査官はできる限りクレームを明瞭にするように努めるとしている。依って、Nautilus判決は出願審査において適用される基準ではない(MPEP

2173.02 を参照されたい)。

|

さらに補足すると、クレームで「・・・に有効な量

(“effective amount”)」という用語は比較的多くの判例でも112条2項の要件を満たすと判断されている(MPEP2173.02

IIIを参照)。

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■

判決の概要:

|

BASFはUSP8524185の特許権者で、競合社Johnsonが185特許を侵害しているという理由でデラウエア地区連邦地裁に訴訟を提起した。地裁は、185特許クレーム1の「触媒作用を起こすのに有効な材料組成物」という用語は112条第2項の要件(クレームの明瞭性の要件)を満たさないとしてクレームは無効であると判示した。当該判決を不服としBASFはCAFCに控訴し、本判決に至った。CAFCは2014年の最高裁判決(Nautilus)の新規判断基準(当業者に合理的な確証を与えるレベルの明瞭性:”reasonable

certainty”)に鑑みても問題となった用語の意味合いは明細書及び当業者の知識に鑑み明瞭であるとして地裁判決を破棄した。

|

特許権者:BASF

CORPORATION

被疑侵害者:JOHNSON

METTHEY INC.

特許:USP 8,524,185

特許発明の概要:

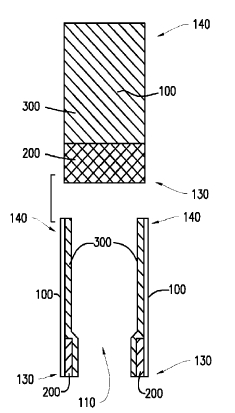

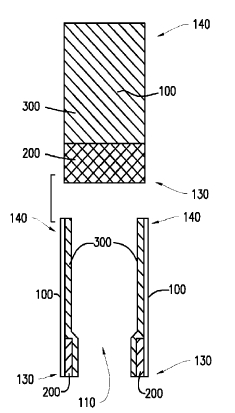

NOxを含む排ガスを処理するための触媒システムに関し、以下図に示すように基材100は上流側(図の上、入口140)〜下流側(図の下、出口130)に延設し、その下流側にはNH3の酸化反応に触媒作用を起こすのに有効な材料組成物Aを含む下塗コーティング層200と基材100の全長に渡り(入口から出口まで)NOxの選択的触媒還元(SCR)に触媒作用を起こすのに有効な材料組成物Bを含む上塗コーティング層300により構成される、即ち、基材100の下流側130のみ下塗200と上塗り300の2層構造である。

|

代表的なクレーム:

|

クレームに対応する図面

|

185特許のクレーム1(参照図番は筆者挿入)

|

|

|

A catalyst system for treating an exhaust gas stream containing

NOx, the system comprising:

at least one monolithic catalyst substrate (100) having an inlet end

(140) and an

outlet end (130); an undercoat washcoat layer

(200) coated on

one the outlet end (130) of the monolithic substrate

(100) and which

covers less than 100% of the total length of the monolithic substrate (100), and containing a

material composition A

effective for catalyzing NH3 oxidation;

an overcoat washcoat layer

(300) coated over

a total length of the monolithic substrate

(100) from the

inlet end (140) to the outlet end (130)

sufficient to

overlay the undercoat washcoat layer (200), and

containing a material composition B

effective to catalyze selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOx; and

wherein material composition A and material composition B are

maintained as physically separate catalytic compositions.

|

|

争点:

Under Nautilus, the question presented here is this: would

the “composition effective to catalyze” language, understood in light of the

rest of the patent and the knowledge of the ordinary skilled artisan, have given

a person of ordinary skill in the art a reasonably certain understanding of what

compositions are covered?

|

クレーム1の”composition

effective to catalyze (触媒作用を起こすのに有効な組成物)”という用語は、明細書の説明及び当業者の知識に鑑み、どのような組成物がそれに該当するのか当業者が合理的な確証をもって理解できるのか?

|

2014年の最高裁判決、Nautilusが112条第2項で規定されたクレームの明瞭性に対する判例法である。同判決によると、明細書及び経過書類を参酌したうえでクレームの権利範囲を当業者に対して「合理的な確証」を与える程度に伝えることができない場合には、クレームは不明瞭である。「合理的な確証」という意味は絶対的或いは数学的な正確さを要求するものではない。112条2項で無効を主張する側が「明白且つ説得性のある挙証基準で」証明する義務を負う。

The Supreme Court in Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc.

held that a patent claim is indefinite if, when “read in light of the

specification delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, [the claim]

fail[s] to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the

scope of the invention.” ––– U.S.

––––, 134 S.Ct. 2120, 2124, 189 L.Ed.2d 37 (2014).

“Reasonable certainty” does not require “absolute or mathematical

precision.” Biosig Instruments, Inc. v. Nautilus, Inc., 783 F.3d 1374,

1381 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (internal quotation marks omitted). Johnson had the burden

of proving indefiniteness by clear and convincing evidence. Id. at 1377.

|

185特許クレームが引例に対して特許性が認められた理由は、185特許の明細書からも明らかなように、SCR及びAMOx触媒の配置によるものであって、それら触媒作用を実現するための特定の触媒に対するものではないことが明らかである。地裁はこの点を認識していない。然るに、明細書及びクレームはSCR及びAMOx触媒を当業者に周知のものの中から選択することを意図している。明細書にそのような触媒作用を実現するための触媒の例示が明細書に詳細に開示されている。地裁はこの点も失念している。

The district court's analysis does not consider that the

specification makes clear that it is the arrangement of the SCR and AMOx

catalysts, rather than the selection of particular catalysts, that purportedly

renders the inventions claimed in the '185 patent a patentable advance over the

prior art. As a result, the claims and specification let the public know that

any known SCR and AMOx catalysts can be used as long as they play their claimed

role in the claimed architecture. The district court's analysis also does not

address the significance of the facts that both the claims and specification

provide exemplary material compositions that are “effective” to catalyze the

SCR of NOx and the oxidation of ammonia, disclose the chemical reactions that

define the “SCR function” and “NH3 oxidation function,” '185 patent,

col. 5, lines 33–49, and illustrate through figures, tables, and

accompanying descriptions how the purportedly novel arrangement of the catalysts

results in improved percent conversion of ammonia and improved nitrogen

selectivity, see id., cols. 13–19.

|

依って、「触媒作用を起こするのに有効な材料組成物」というクレームの表現はNautilus基準を満たす。故に地裁判決を破棄差戻しとする。

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■|

|

References

|

112条(2)項:

The specification shall conclude with one

or more claims particularly pointing

out and distinctly

claiming the subject matter which the applicant regards as his

invention.

|

Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc.(2014年最高裁判決)

The Supreme Court in Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc.

held that a patent claim is indefinite if, when “read in light of the

specification delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, [the claim]

fail[s] to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the

scope of the invention.” ––– U.S.

––––, 134 S.Ct. 2120, 2124, 189 L.Ed.2d 37 (2014).

“Reasonable certainty” does not require “absolute or mathematical

precision.” Biosig Instruments, Inc. v. Nautilus, Inc., 783 F.3d 1374,

1381 (Fed. Cir. 2015) (internal quotation marks omitted).

|

MPEP

2173.02 Determining Whether Claim Language is Definite [R-07.2015]

[Editor Note: This MPEP section is applicable

to applications subject to the first inventor to file (FITF) provisions of the

AIA except that the relevant date is the "effective filing date" of

the claimed invention instead of the "time the invention was made,"

which is only applicable to applications subject to pre-AIA

35 U.S.C. 102.

See 35

U.S.C. 100 (note)

and MPEP

§ 2150 et

seq.]

During prosecution, applicant has an

opportunity and a duty to amend ambiguous claims to clearly and precisely define

the metes and bounds of the claimed invention. The claim places the public on

notice of the scope of the patentee’s right to exclude. See, e.g., Johnson

& Johnston Assoc. Inc. v. R.E. Serv. Co., 285 F.3d 1046, 1052, 62 USPQ2d

1225, 1228 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (en banc). As the Federal Circuit stated in Halliburton

Energy Servs., Inc. v. M-I LLC, 514 F.3d 1244, 1255, 85 USPQ2d 1654, 1663

(Fed. Cir. 2008):

We note that the patent drafter is in the best

position to resolve the ambiguity in the patent claims, and it is highly

desirable that patent examiners demand that applicants do so in appropriate

circumstances so that the patent can be amended during prosecution rather than

attempting to resolve the ambiguity in litigation.

|

I.

CLAIMS UNDER

EXAMINATION ARE CONSTRUED DIFFERENTLY THAN PATENTED CLAIMS

Patented claims

are not given the broadest reasonable interpretation during court proceedings

involving infringement and validity, and can be interpreted based on a fully

developed prosecution record. While "absolute precision is unattainable" in

patented claims, the definiteness requirement "mandates clarity." Nautilus,

Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., 527 U.S. __, 134 S. Ct. 2120, 2129, 110

USPQ2d 1688, 1693 (2014). A court will not find a patented claim indefinite

unless the claim interpreted in light of the specification and the prosecution

history fails to "inform those skilled in the art about the scope of the

invention with reasonable certainty." Id. at 1689.

|

The

Office does not interpret claims when examining patent applications in the same

manner as the courts. In

re Packard, 751 F.3d 1307, 1312, 110 USPQ2d 1785, 1788 (Fed. Cir. 2014); In

re Morris, 127 F.3d 1048, 1054, 44 USPQ2d 1023, 1028 (Fed. Cir. 1997); In

re Zletz, 893 F.2d 319, 321-22 (Fed. Cir. 1989). The Office construes claims

by giving them their broadest reasonable interpretation during prosecution in an

effort to establish a clear record of what the applicant intends to claim. Such

claim construction during prosecution may effectively result in a lower

threshold for ambiguity than a court's determination. Packard, 751 F.3d

at 1323-24, 110 USPQ2d at 1796-97 (Plager, J., concurring). However, applicant

has the ability to amend the claims during prosecution to ensure that the

meaning of the language is clear and definite prior to issuance or provide a

persuasive explanation (with evidence as necessary) that a person of ordinary

skill in the art would not consider the claim language unclear. In re Buszard,

504 F.3d 1364, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2007)( claims are given their broadest reasonable

interpretation during prosecution “to facilitate sharpening and clarifying the

claims at the application stage”); see also In re Yamamoto, 740 F.2d

1569, 1571 (Fed. Cir. 1984); In re Zletz, 893 F.2d 319, 322, 13 USPQ2d 1320,

1322 (Fed. Cir. 1989).

See MPEP

§ 2111et

seq. for a detailed discussion of claim interpretation during

the examination process. The lower threshold is also applied because the patent

record is in development and not fixed during examination, and the agency does

not rely on it for interpreting claims. Packard, 751 F.3d at 1325 (Plager,

J., concurring). Burlington Indus. Inc. v. Quigg, 822 F.2d 1581, 1583, 3

USPQ2d 1436, 1438 (Fed. Cir. 1987) (“Issues of judicial claim construction

such as arise after patent issuance, for example during infringement litigation,

have no place in prosecution of pending claims before the PTO, when any

ambiguity or excessive breadth may be corrected by merely changing the

claim.”).

|

During examination, after applying the broadest reasonable

interpretation to the claim, if the metes and bounds of the claimed invention

are not clear, the claim is indefinite and should be rejected. Packard, 751 F.3d at 1310 (“[W]hen the USPTO has initially

issued a well-grounded rejection that identifies ways in which language in a

claim is ambiguous, vague, incoherent, opaque, or otherwise unclear in

describing and defining the claimed invention, and thereafter the applicant

fails to provide a satisfactory response, the USPTO can properly reject the

claim as failing to meet the statutory requirements of §

112(b).”); Zletz, 893 F.2d at 322, 13 USPQ2d at 1322.

For example, if the language of a claim, given its broadest reasonable

interpretation, is such that a person of ordinary skill in the relevant art

would read it with more than one reasonable interpretation, then a rejection

under 35

U.S.C. 112(b) or pre-AIA

35 U.S.C. 112,

second paragraph is appropriate. Examiners, however, are cautioned against

confusing claim breadth with claim indefiniteness. A broad claim is not

indefinite merely because it encompasses a wide scope of subject matter provided

the scope is clearly defined. Instead, a claim is indefinite when the boundaries

of the protected subject matter are not clearly delineated and the scope is

unclear. For example, a genus claim that covers multiple species is broad, but

is not indefinite because of its breadth, which is otherwise clear. But a genus

claim that could be interpreted in such a way that it is not clear which species

are covered would be indefinite (e.g., because there is more than one reasonable

interpretation of what species are included in the claim). See MPEP

§ 2173.05(h),

subsection I., for more information regarding the determination of whether a

Markush claim satisfies the requirements of 35

U.S.C. 112(b) or pre-AIA

35 U.S.C. 112,

second paragraph

|

MPEP 2173.05(c) Numerical Ranges

and Amounts Limitations

III.

“EFFECTIVE

AMOUNT”

The

common phrase “an effective amount” may or may not be indefinite. The proper

test is whether or not one skilled in the art could determine specific values

for the amount based on the disclosure. See In reMattison, 509 F.2d 563,

184 USPQ 484 (CCPA 1975). The phrase “an effective amount . . . for growth

stimulation” was held to be definite where the amount was not critical and

those skilled in the art would be able to determine from the written disclosure,

including the examples, what an effective amount is. In reHalleck, 422

F.2d 911, 164 USPQ 647 (CCPA 1970). The phrase “an effective amount” has

been held to be indefinite when the claim fails to state the function which is

to be achieved and more than one effect can be implied from the specification or

the relevant art. In reFredericksen, 213 F.2d 547, 102 USPQ 35 (CCPA

1954). The more recent cases have tended to accept a limitation such as “an

effective amount” as being definite when read in light of the supporting

disclosure and in the absence of any prior art which would give rise to

uncertainty about the scope of the claim. In Ex parteSkuballa, 12 USPQ2d

1570 (Bd. Pat. App. & Inter. 1989), the Board held that a pharmaceutical

composition claim which recited an “effective amount of a compound of claim

1” without stating the function to be achieved was definite, particularly when

read in light of the supporting disclosure which provided guidelines as to the

intended utilities and how the uses could be effected.

|